|

This illustration, from the cover of [Locke], shows the quipu long-knot representing the number 3.

|

Quipus or khipus are a recording medium developed by the Inca

and their predecessors (our earliest examples date back to

about 900 AD; many details of their use were unfortunately obliterated

during and after the Conquest, in the early XVI century; there are about

600 quipus [Urton] known to exist today, mostly in museums).

Signs in this medium are knots in strings. This illustration, from the cover of [Locke], shows the quipu long-knot representing the number 3. |

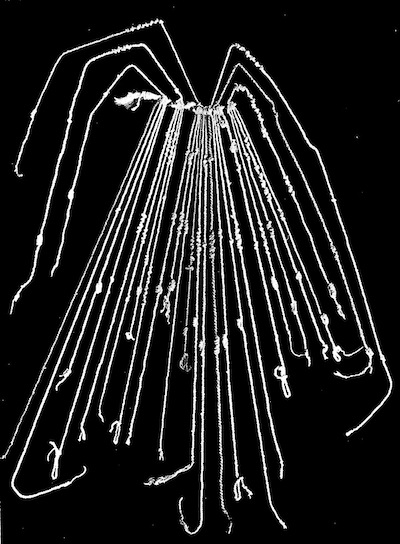

Left: a numerical

quipu in the collection of the American Museum of

Natural History, New York (Accession No. B-8713).

In this example

the pendents have no subsidiaries, but six top cords are

attached so as to group the pendants four by four.

As

Locke's analysis shows,

each top cord records the sum of the numbers encoded in knots

on the four pendents

in its group. This item, which Locke describes as

"an example of the most highly developed form of the quipu,"

appears as the frontispiece to his work [Locke]. An even more

intricate numerical relation, this time between different

quipus, all found together, has been recently documented in

[Urton and Brezine].

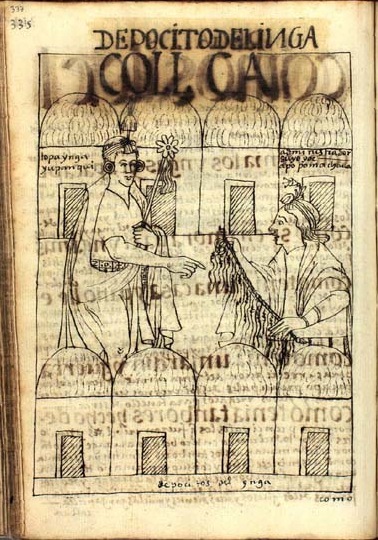

Right: Locke does not give the dimensions of that

quipu, but they may be guessed by comparison with the quipu shown

(with some of its knots visible) in this page from

El primer nueva corónica y

buen gobierno, by

Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala (1615). Image from the Guaman

Poma Website,

Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark, used under

Creative

Commons License. Caption: Storehouses of the Inca. We see an

administrador, identified as Poma Chaua (an ancestor of the author)

showing a quipu, presumably with some tally of the storehouses' contents,

to Topa Inca Yupanqui (1471-93). Text is in Spanish and Quechua.

A quipu is a portable device made of (cotton or camelid wool) string in a two-dimensional array. A primary cord (also, main cord, transverse cord) "varying in length from a few centimeters to a meter or more" [Locke] supports several pendents (also, pendant cords) "seldom exceeding 0.5 meter in length" [Locke]; up to 1500 in the largest examples, but typically in the range from a few to several hundred. The pendents can bear subsidiary cords, which themselves can have subsidiaries, and so on, up to six levels in some instances [Ascher]. There may also be a set of top cords, attached so as to lie most naturally on the opposite side from the pendents. The pendents, subsidiaries and top cords each carry a sequence of knots, which record information.

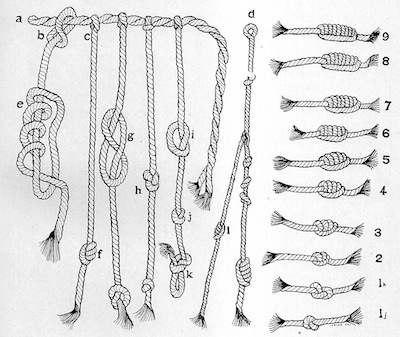

Locke's portrayal of primary cord, pendents and susidiaries, and of the three types of information-bearing knots that appear in standard ancient quipus: the overhand knot (i, j, 1j), the figure-eight knot (g, h, 1h), and the long knots tied as an overhand knot but casting the end through the loop from 2 to 9 times (2, ..., 9; 4 is shown loosened as e, and tied in the subsidiary as l; 3 also appears on a pendent as f, and 5 appears on pendent d which, without its subsidiary, encodes the number 135. As remarked in [Urton], each of these knots can be tied either right-hand or left-hand.

The different levels are apparent in Locke's photograph, and even more precisely demarcated in the six-figure example linked to just above. As in Old Babylonian notation, the lack of a symbol for zero introduces a theoretically possible ambiguity: 210 and 2100 alone cannot be distinguished. But if just one cord in a quipu displays a number with a non-zero units place, then the distinctive knots used for that position, and the coherence of levels, will anchor the entire array. The ideal even spacing between levels shown in the six-figure example could compensate the (unlikely) absence of non-zero entries, in any position higher than units, across an entire quipu.

To a topologist, the knots in quipus are quite standard. When the two free ends of the overhand knot are joined the configuration forms the trefoil knot, knot $3_1$ in the standard knot table. Similarly the figure-eight knot appears as $4_1$. The first few long knots are in the table: the quipu knot 2 is $5_1$, 3 gives $7_1$ and 4 gives $9_1$. There are 165 distinct knots with 10 crossings; the table stops there. But if it went on, presumably the quipu 5 would correspond to $11_1$, ..., and 9 to $19_1$ since these torus knots are the simplest in each case.

Locke's loosened 4-knot, captured in a loop, can be deformed to the standard picture of $9_1$.

Each of the torus knots $3_1$, ..., $19_1$ exists in two mirror-image forms, distinct in that one cannot be deformed to the other. All 18 of these forms exist in the corpus of ancient quipu knots ([Urton], Chapter 3).

The figure-eight knot also exists in quipus in two mirror-image forms.

In [Urton] the two ways of tying a figure-eight knot in a cord are described as an S-knot (a. and b., front and back) or a Z-knot (c. and d.), in analogy with the two directions in which yarn can be spun.

The figure-eight knot is different from all the overhand knots in that its two mirror-image forms are topologically equivalent. The deformation requires loosening the knots and flipping selected loops over or under the rest of the knot.

The deformation from the S-knot figure-eight (form b.) to the Z-knot (form c.). In step 1, the red loop is flipped over the rest of the knot; in step 2, the blue loop is flipped under.

|

The 3-turn friar's knot (two views), compared with the quipu long knot representing the number 3. These knots (both tied left-handed here) are topologically the same. |

|

|

Detail of a fresco (painted 1297-1300 and sometimes attributed to Giotto) in the Upper Church of San Francesco in Assisi; the saint is shown wearing the habit and cincture of his followers. In particular the cincture has distinctive knots in the hanging end. |

Garcilaso de la Vega's Commentarios Reales de los Incas (Lisbon,

1609) describe quipus in some detail. In particular (as quoted in [Locke,

p. 40]) "... the knots for each number were made together in one company, like

the knots represented in the girdle of the ever blessed Patriarch, St.

Francis." Franciscan friars still wear such a belt; traditionally the

knots are three, representing vows of poverty, chastity and

obedience. In fact, these knots are topologically identical to

long knots in quipu, but they are tied so as to be symmetric and

consequently do not look the same.

The rule for tying one of the

long knots is given in [Locke]: "It is formed by tying

the overhand knot and passing the end through the loop of the knot as

many times as there are units to be denoted. One end in then drawn taut, thus

coiling the other about the strand the required number of times." The rule

for tying one of the friar's knots is given in great detail

here and is nicely explained by Friar Stephen Agosto of the Orthodox

Anglican Society of St. Francis, in this

video.

|

|

Friar Agosto's method for tying a Franciscan cincture knot: stretch out a length of cord; wind backwards the number of turns wanted; lead the working end of the cord through the tube thus created. As the knot is pulled tight, it must be gently massaged to keep the symmetrical shape. |

|

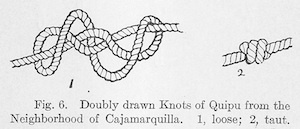

Friar's knots are sometimes found in quipus: [Locke] gives an

example, apparently typical of "the Neighborhood of Cajamarquilla,"

of a friar's knot with three turns. Locke does not approve of this

method: "... the peculiar wrapped condition shown in Fig. 6 [here

reproduced on the left]... together

with the softness of the cord, produces

a knot in which it is hardly possible to note the number of turns." Locke's

taut knot is the same as the three-turn friar's knot shown at the start of this

section, but tied right-handed. These knots are also mentioned in [Ashley], under "Single-Strand Stopper or Terminal Knots," as item #517: "A Threefold overhand knot or even a larger one, may be tied, but beyond two turns the knot must be worked into shape, and for that reason it may be considered more decorative than practical." Ashley draws the loose knot as Locke's 4 above (but with 7 crossings), and the compact form exactly as Locke's knot from Cajamarquilla (except with the opposite handedness in both cases). |

The equivalence between the quipu knots and the friar's knots with the same number of turns is not completely obvious. To maneuver one to the other in space requires some energetic twisting.

These knot projections show steps in the deformation from the 3-ring friar's knot to the torus knot $7_1$ and the quipu knot 3. The middle winding has been colored red for easier reading.

The "energetic twisting" required to deform a friar's knot into the corresponding long knot can be quantified mathematically, using the writhe. This is an integer, associated to a knot, that measures its geometrical complexity. The writhe can be defined from a planar projection of the knot; it is not a topological invariant.

| The writhe of a knot is calculated from a knot projection

diagram by choosing

a direction on the string; then (see illustration at left)

an integer is asigned to each crossing:

$+1$ if the rotation from overcrossing direction to

undercrossing direction is

to the left (counterclockwise); $-1$ if it is to the right. The writhe

is the sum of all these integers. It does not depend on the

choice of string direction, but changing the handedness (interchanging

over- and under-crossings throughout the knot) reverses the sign of the

writhe. The writhe is invariant under sliding moves, but changes by $1$ each time an independent loop is formed or eliminated. |

Some knots and their writhes. The standard

figure-eight (without any extra independent loops) has writhe $0$.

The overhand knot has writhe $+3$ if it is tied left-handed, and $-3$

if it is tied right-handed.

The friar's knot with three turns (tied

right-handed) has writhe $-12$, while the topologically equivalent

quipu long-knot 3 has writhe $-7$. In fact during the

deformation from one to the other shown in steps a. through j.

above, five separate independent loops are untwisted. This

accounts exactly for the change in writhe, and explains how the

effort required to carry out the deformation between actual

knots will vary with the torsional rigidity of the cord.

Note: revised, May 5, 2014. The revision corrects an error in the original account of the topology of the figure-eight knot. Thanks to Prof. Ian Agol for bringing the error to our attention.

References

[Ascher] Martha Ascher and Robert Ascher, Code of the Quipu,

University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1981

[Ashley] Clifford W. Ashley, The Ashley Book of Knots. Douibleday,

New York, 1944

[Locke] L. Leland Locke, The Ancient Quipu, The American Museum

of Natural History, New York, 1923

[Mackey] Carol J. Mackey, Knot Records in Ancient and Modern Peru,

Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, Department of Anthropology, 1970.

(University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, 1976)

[Urton] Gary Urton, Signs of the Inka Khipu, University of Texas

Press, Austin, 2003

[Urton and Brezine] Gary Urton and Carrie J. Brezine, Khipu Accounting

in Ancient Peru, Science 309 (2005) 1065-1067